How Long Gone Podcast Host & Writer Chris Black On The Art of Conversation

Portrait by Cobey Arner

Interview by James Wright

Chris Black is one half of How Long Gone, a podcast co-hosted with friend and DJ, Jason Stewart. Started during the pandemic, HLG has managed to succeed when almost all Covid-era podcasts disappeared without a trace. Now clocking-in at a heady 783 episodes, with guests ranging from Brett Easton Ellis to Charli XCX, Graydon Carter to Zane Lowe, the show has developed a reputation for being distinctly unapologetic. Dry, hilarious and culturally omnivorous, Chris and Jason’s taste and insider gossip zags around the culture, but also the merits and drawbacks of Delta One lounges, sobriety, 4 Charles and Waymos. Unlike almost every other vaguely celebrity/insider podcast, HLG is a show driven by the hosts – it’s their tone that guides the conversation, not that of the guests.

What’s most striking in-conversation, is how clear-eyed he is about the concept of value. Outside of podcasting, Black has built a writing and consultancy career on a bedrock of taste, trust, and relationships – and knows how to make that legible to the right people. Whether he’s working with J.Crew, shaping the visuals for Leon Bridges' album, or trading stories about the pitfalls of the fashion industry, Black brings the same sensibility: an appreciation for substance over flash, for collaboration over ego, and for getting things done.

We spoke with Chris on what it means to be a creative consultant today, transatlantic culture clashes, why constraints make for better work, and how not to be an asshole in a room full of people who assume you are.

I don’t think every creative person should be given full license to do whatever they want. Boundaries—or restrictions—can breed greater creativity

James Wright: It’s always interesting interviewing people who interview people for a living. Do you look forward to talking with journalists and editors on How Long Gone or for GQ?

Chris Black: For me, there are people who are so good at it, that every now and then, I feel like an amateur—no matter how many hours I’ve clocked. I can talk, sure, but it’s mostly with people I hang out with socially, who happen to be really accomplished writers. Even at dinner, the way they communicate is so sharp — they’re inquisitive, and they know how to move a conversation along. I get it now, how that works.

JW: I’m biased, but your episodes with editors—whether it’s Gert Jonkers, Penny Martin or Graydon Carter — are ‘inside baseball’, yes, but genuinely insightful. Do you think there’s a distinction between talking to editors and journalists? Journalists can be — oddly, and sort of paradoxically — not great at being interviewed.

CB: Definitely. Whether I’m doing an interview for How Long Gone or for GQ, I’m often surprised by who’s great and who’s not. It’s usually the people you wouldn’t expect who end up giving you exactly what you want—or have you in stitches, or whatever the case may be. They deliver, which is always a nice surprise.

JW: I find authors to be the most intimidating.

CB: What matters to me, is that the person is interesting to me, not the subject. That’s why I don’t really bother reading a book, let's say, unless it’s a book I’d actually want to read. That said, sometimes when something becomes really big or successful, I find it compelling no matter what the subject is. But if it’s a musician I’ve loved forever or grew up listening to, that’s when I get nervous. It’s been part of my life for decades, and that makes it more emotionally loaded — and more challenging.

Chris and Jason at the Four Seasons in Chicago before their show

JW: Looking through your archives, I was surprised to see how many of the same people we’ve interviewed or featured: Father John Misty, Christopher Owens, Kurt Vile, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Weyes Blood and on and on.

CB: Father John Misty is probably one of the most entertaining interviews I’ve ever done. He’s unbelievable. We actually became friendly and he invited me to see him open for Kacey Musgraves. The only date I could make was in Grand Rapids, Michigan, so I flew out for the night, hung out with him, took some photos, and caught the show.

At one point, he told me he’d stopped doing press tours because they started to overshadow the music – 'Because I say crazy shit, and I’m smart, that’s what people want.' And that’s great. But this new record has been so well received and critically acclaimed, I think he might feel more comfortable stepping back into that space. He’s kind of a dying breed—there aren’t many artists left who have both the musical chops and the personality. He looks incredible, he’s a rock star, and I don’t think we see that very often anymore.

JW: Honestly, even if he had PR training, I don’t think he’d be able to use it. He’s ‘unfiltered’ — and like you said, smart and quick-witted.

CB: And that’s our approach. We obviously work around press cycles to some extent — because that’s when people are available — but we rarely lean into that unless there’s a real reason to. There has to be something compelling beyond just ‘I made this album.’ Some guests come in prepared to steer clear of that kind of conversation, and honestly, they could do that in a PR setting. But that’s not what we do.

JW: When it comes to the cadence and tone of How Long Gone, do you convey the gist to guests upfront, or do you just presuppose that they’ll get it?

CB: Jason and I have had this exact discussion. It’s like, we’re going to do this whether you’re here or not. You can either play along and have fun, or you can sit there like a bump on a log — but we’re still going to have fun. It doesn’t matter who’s on the other side of the conversation. Sometimes, within the first ten minutes, you can tell someone’s a little confused or glazed over and can’t quite snap into it. But then there are others who immediately get it. They realise we’re just here to bullshit — not catch them in anything or make fun of them. The dream scenario for us is someone like Lukas Gage. He’s funny, he listens all the time, and he knew exactly what to do. But then you have someone like Nancy Silverton, who’s never heard of us — and both situations are equally good for different reasons.

Jason and I always try to treat each guest with respect, while still having fun. We’re going to be funny, we’re going to poke the bear, but it’s never from a bad place. Ultimately, it’s all for the betterment of the show

JW: I was going to bring up the Lukas episode.

CB: That’s a guy who’s more of a friend of a friend. I’d never met him, and I’d never seen White Lotus. I knew who he was, of course, but I had no idea how funny and cool he was — or how much he’d have the right attitude for us. He was willing to play ball.

JW: I also recently listened to the Bella Freud episode – a contrast to the Lukas episode...

CB: Since I work in fashion, I find people like Bella especially interesting, partly because they have the kind of audience that’s tough to keep. Bella is smart, and her podcast is well produced. It’s 12 episodes in now, and it’s the only ‘fashion’ podcast that’s actually good. I’d love to talk to someone like Nick Cave or Juergen Teller — guests that Bella’s had on her show, so, going into that interview, there’s already a mutual respect and understanding. She has a specific way of speaking, almost calming, but she’s also funny. Something people might not expect because her podcast comes across as pretty serious when you look at it on the surface.

JW: Why do you think fashion hasn’t really carved-out its own space in podcasting?

CB: Most fashion podcasts come from pre-existing publications like Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, which forces a certain set of rules and preconceived notions. On the other hand, independents tend to be either too niche or feel like they’re done by someone who isn’t comfortable being an outsider. To be in the position of an insider — curious, cool, and not too self-serious — is a tough balance to find. Bella does that, even though she may come off as super serious at first.

JW: There’s also this weird coda — an unspoken set of rules within fashion that I think exists in film and music to some degree, but in fashion, it’s taken much more seriously. It doesn’t do self-effacing in quite the same way.

CB: I’d love to talk to Jonathan Anderson — he’s smart but clearly has a sense of humour, which you can see in his clothes. Or Marc Jacobs, who’s hilarious. Though, I don’t expect someone like Margiela or John Galliano to be super chatty! We’ve been trying to talk to Jonathan for a year or two now. Someone on the US team sees the value in it and thinks it’s a good opportunity for him, but then when it gets to his European team, it’s like, 'What the fuck is this?' I get the disconnect. I don’t really see How Long Gone resonating with communication directors in Paris — it’s not necessarily our market, and that’s fine.

There are certain things I don’t worry about too much because I believe the time will come. We’ve reached a point I’m proud of in the music space. I’ve had a lot of managers, agents, and artists tell me that How Long Gone is something they have to do. Music was our immediate focus because it’s Jason’s and my background—it’s still a huge part of our lives, both professionally and socially. A lot of the people we’ve had on the show are close friends, which is a gift. But I’d love to expand into the art and fashion worlds, and have How Long Gone be seen as a place you have to come on.

Audio equipment in Philadelphia

JW: You can’t get higher praise than someone saying How Long Gone is a show that musicians have to do. That’s pretty cool.

CB: It’s really good. I can talk to Johnny Marr or Cat Power — people I’ve spent my whole life listening to. We do so many shows and talk to so many people that you forget. Which is kind of fucked up, but it’s true. When you do as many shows as we do, it’s hard to think about anything but the next thing. You just have to keep moving and keep going.

JW: Jason does the editing and you handle the talent outreach?

CB: Jason handles the editing and the artwork for every episode, while the talent is more my responsibility. Jason participates when he has an idea, though. We recorded with Chanel Beads today, a musician Jason loves. Occasionally, our tastes align, from Waxahatchee to Chanel Beads, and it was Jason who reached out to them. But a lot of it is fielding, which can actually be really great. We’ve spoken to a lot of people we wouldn’t have considered before we got the press release. Ultimately, a lot of it comes from what we like and who we want to talk to. It doesn’t matter if they’re promoting something current, which is why we’re able to do three episodes a week.

JW: How did you find learning the process of booking or pitching someone, and moving through that back-and-forth that’s difficult to navigate?

CB: At first, it was all people we knew. It was Covid, so there was a mix of people having nothing to do and knowing it was a relatively safe space. Everyone we were initially speaking to knew at least one of us. Then we started to build momentum, and that made it easier to reach out to people. Sometimes we’d have to explain ourselves, go beyond just including a hyperlink to a press release about the show. But now, we’ve reached this interesting point where at least one person in their life knows what How Long Gone is and can explain it to them. A few times, someone has said, 'Don’t do it, you’ll get eaten alive.' I approach that with a bit of disbelief, because no matter who you are, Jason and I always try to treat each guest with respect, while still having fun. We’re going to be funny, we’re going to poke the bear, but it’s never from a bad place. Ultimately, it’s all for the betterment of the show.

Creative direction means so many different things now, depending on who you ask. I don’t have Photoshop. I don’t know how to use Figma. But I know what’s good and what’s bad. And to me, that’s what gets a project to the place where it works

JW: People can be a bit apprehensive, sometimes even admitting they’re nervous about doing the show, which is almost amusing because, at the end of the day, they always relax into it. They’re going to get more comfortable. I interviewed Jaime Perlman recently, and she admitted to cancelling on you twice out of nervousness.

CB: We’re used to that. Jaime — she’s a legend. I love her work, but she’s also got a lot of personality and a great attitude. But I get it. I also think there are people like Jaime who come from the other side of things, and that’s part of why she’s in her head. People like her, regardless of their position, I find we have a lot in common. We’re usually in the same age range, so there’s always some overlap in music and TV, regardless of their career. It’s always interesting.

JW: You’ve mentioned that your focus and reputation were built in music, while I know film follows a more mechanical process, with publicists and long email chains before you even get to a shoot or interview. Have you analysed what role Hollywood and film should play in the show?

CB: Famously, I don’t care about movies. I’ll watch films that make sense to me, but they’re not my passion. I think that’s why we haven’t fully crossed into that world yet. There are also things in the How Long Gone universe that take less time and effort to bring to fruition — like answering five questions for a newsletter—compared to film, which is much harder to navigate and where people are taken very seriously.

But still, you see Timothée Chalamet go on Theo Von and he’s amazing. I’d love to have Timmy on our show, I think it makes a lot of sense, and I believe we can get there. It’s about figuring it out, having a few people in that corner of the world pushing for it, and then it all starts.

JW: Given the tone of your podcast, there was something you and Jason said the other day about how it’s harder to remain apolitical. Do you envision a world where you invite AOC onto How Long Gone? And have a conversation where you take that same style of conviviality and informality to topics that would normally feel heavy?

CB: I love a challenge, and I’d definitely be up for something like that. AOC would be someone I’d make fun of because, honestly, there are things she does that should be made fun of. But she’s also in that position for a reason, and has interesting things to say. I just don’t think it’s a natural part of what we do. I write about politics in my columns when it’s central to the point, but it’s not something that comes naturally. So, it doesn’t come up. We pay attention, we know what’s going on, but there are so many people talking politics — we don’t need to add to that, especially when we’re talking to a guitar player.

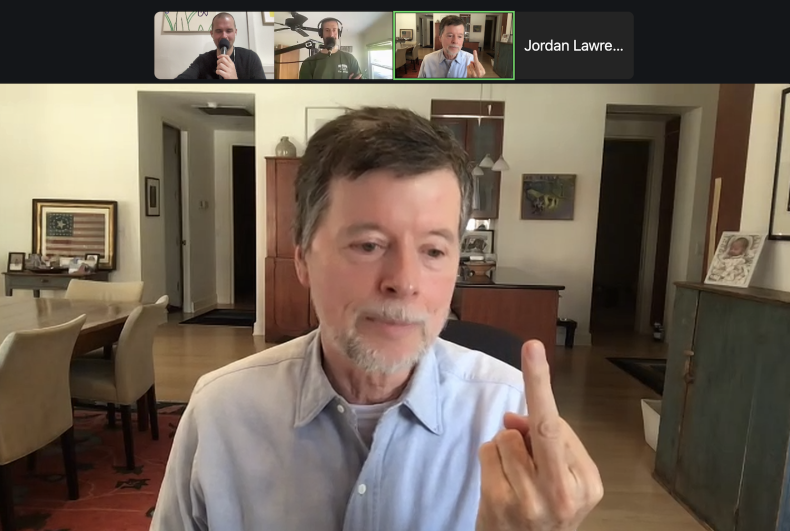

Jason getting ready for the Emmy Awards

JW: I guess your reflection on the moment and what’s going on is more by osmosis — it naturally becomes part of what you end up chatting about.

CB: Yes, totally. That feels natural and normal to me.

JW: Speaking of your approach to reaching people and having a dialogue, have you ever considered filming the episodes?

CB: We've talked about it. We’ve left a lot of money on the table because we want to do things our way. It’s partly because of our age, how we were raised, and what we think is cool and important. The show as it is doesn’t lend itself to video.

I’m in New York, Jason’s in LA, and I’ve recorded from every country and time zone you can think of. I don’t want to limit my life just to be in the garage with Jason twice a week. If we were going to film it, it would have to look a certain way. It would cost a lot of money, take a lot of time and effort, which would change the whole dynamic of the show. If we decided to go down that path, we’d create something different, geared for TV or YouTube. The concept would be separate from the podcast, so the podcast could remain free.

JW: Given the frequency of the show, what’s the structure of each episode? Do you research, or is it mostly off-the-cuff?

CB: Jason does the research, I don’t. Maybe because I’m leading the booking, I’m more familiar with the person, even if it’s just a baseline understanding. Jason does a great job going through their Twitter, checking little things so that if there’s a lull, he has a thought-starter ready. It’s the same for our live shows — he writes everything down, I don’t see it, we go on stage, and it’s all new to me, so you get to see my real reaction. For example, we have author Sarah Hoover coming on the show this week. I haven’t read her book — I’ve heard it’s amazing, and I do plan on reading it, but even if I didn’t, because it’s not a subject that interests me, I think, ‘What’s the point?’ What’s the point of reading 400 pages if I don’t care about it? But I do think the person is interesting, and that’s what matters. It won’t affect the conversation.

JW: How often are you actually in the same room?

CB: If I'm in LA, I go to his house in Glendale to record in his office, which is nice. If he’s in NYC, we do one here. But we’re not in the same room often. Jason had a podcast before – a show called Tall Tales that became a cult favourite. Back then, he had a rule that guests had to come to his house to record. But after Covid, and how we started the show, that wasn’t possible. Now, this setup feels best for us. Our guards are down because we’re in our own spaces. It doesn’t feel as big a deal, even knowing millions might hear it.

Recording How Long Gone with Ken Burns on Zoom

JW: Does recording feel like a release or escape? Or does it continue to be something you look forward to, even with the demand of recording three shows a week?

CB: Honestly, I think consistency is what sets us apart. I’m almost always looking forward to recording, but it’s different when I’ve been traveling a lot or when I’m in Singapore, waking up at 4am to record. We push ourselves to get it done and make it as entertaining as possible, no matter how we feel or where we are. And that commitment comes through. So, I’m always glad I did it. Keeping our promise to the listeners is really important to us.

JW: Did you guys have an innate confidence when you started? I know Jason had been podcasting for a while, but in terms of speaking to these people — friends or not — has the tone evolved?

CB: I think Jason and I are in a very lucky position where we found each other, and it just works like that. That’s how it’s always been since we became friends, and we found a way to apply that to something bigger than us. And that’s where we are now. The way we talk, how we treat each other, and how we treat our friends — that’s just how we operate. Of course, you play up certain traits in public-facing things because, to some degree, it’s a performance. But the confidence piece? I don’t really see it that way. I respect these people, and often, I’m a fan or I love what they do. But they’re still my equal. I’m not thinking of them as ‘better than me.’ I think that’s why we’ve been successful with the red carpet stuff. I’ll think, ‘Yeah, Diane Lane’s a legend,’ but I’m not going to be shook. I have to talk to Diane Lane for five minutes. I think she’s incredible, but I’m not going to approach her any differently, and neither will Jason. I think that’s why that tone works.

JW: How did red carpets come about?

CB: Partly, it was our relationship with The Bear crew – Chris Storr, Cooper Wade, and Josh Senior, who make the show. Chris is the creator and director, and Josh and Cooper are the producers. I work on the show behind the scenes with licensing and partnerships. Jason and I were on the wall as food critics in the last season, and we’re good friends with Lionel and Ayo. FX knew about our relationship, so they had us host the Red Carpet for the season premiere. That was kind of a proof of concept. Then we did the Emmys with FX and GQ, given our relationship with Will, the editor-in-chief. He knew we could handle it, and it was a big vote of confidence. The live aspect was intense with earpieces, teleprompters — it felt serious but, in some ways, also easier because of the familiarity.

JW: Do you feel that could lead to a natural evolution from that to television?

CB: I think there are a few ways we’ve looked at it. There’s definitely a kind of Weekend Update-style desk vibe, some pre-taped elements where we go out with a celebrity to do something — cooking, gardening, whatever it may be. Then, there’s the musical element, which is something we’ve always wanted. My dream is for every episode to end with a band playing at Electric Lady, because that’s what I think is cool. It’s missing from the current late-night scene. You have Fallon and Kimmel, of course, but I think we could do something more like 120 Minutes or Tom Green’s show — a different take that feels more conversational. I’ve always loved how Father John Misty would go on Letterman, and Letterman would bring him on the couch because he knew it was going to be a good conversation. That’s the kind of vibe I want. Artists we love, not just performing, but sitting down with us for five minutes to really shoot the shit. That’s something I think television is missing, and we could provide.

JW: You see viral internet content and a few shows attempt to do something different, but there is no stronghold for an alternative to the traditional talk show format.

CB: The UK does it best — they have better taste. Having six celebrities on the couch at the Graham Norton Show with Coldplay playing is hilarious, and it would never happen in the US. There are so many places for artists to promote their work, whether it’s video, print, or online, each in different shapes. I think a bit of the old-school approach has been forgotten. Everything’s rushed now—how short can the clip be? How long? That’s important, but thinking in longer formats, rather than just thirty-second clips, could be really beneficial.

JW: You can apply that sentiment to so many things. Like you’ve mentioned before about being a print collector—you can’t throw away any magazines. I think the core belief behind anyone doing something as risky as a print magazine is that there’s still a place for it, and it matters, even in this clippable age.

CB: With magazines in general, I think the younger generation is embracing them and starting to understand their value, kind of like how vinyl became a collector’s item. It’s not going to be a monthly thing anymore—that’s just not what people want. Something more special, that costs more and comes out twice a year, feels more reasonable. And I think that’s why young people are starting to embrace it.

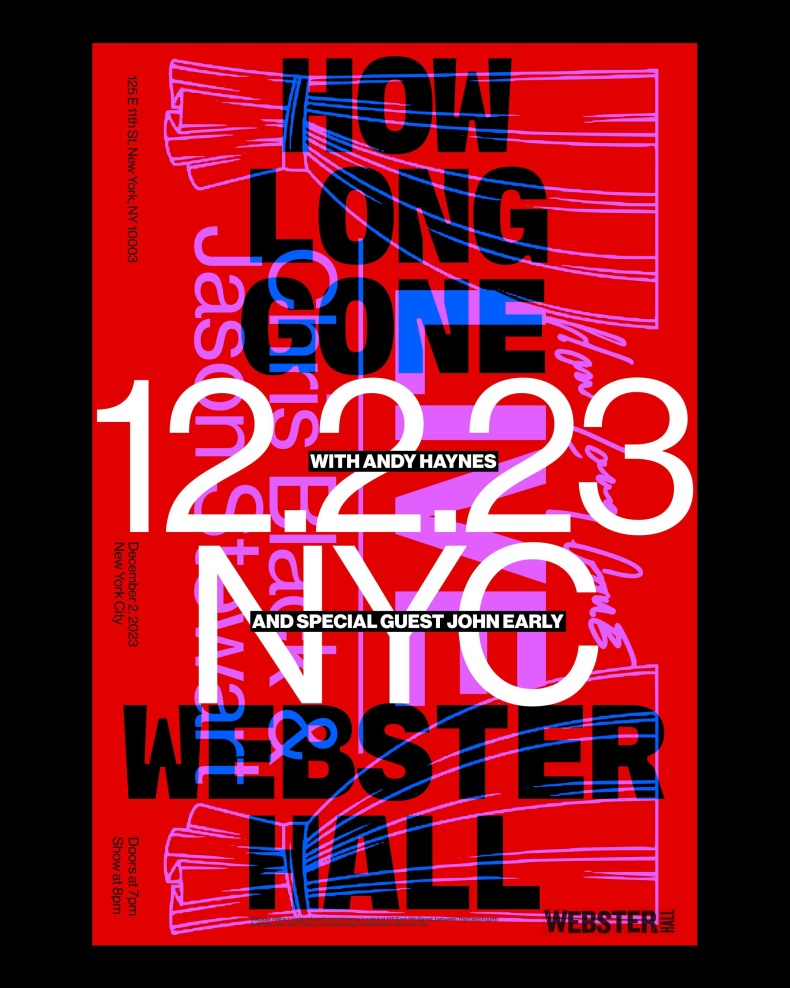

A flyer designed by Sam Jayne for a How Long Gone show at Webster Hall

JW: Absolutely. The issue isn’t whether there’s still some interest in print — there is some. The real challenge lies in the financial piece. Brands today invest so heavily in online and social media, with little focus on print. The struggle became how to create a sustainable business model.

CB: I always encourage my clients to consider print if it makes sense because, in the grand scheme of things, it's a small part of the budget. When you're already spending $200,000 on media, what's an extra 20-30K for a print ad? Especially if it’s part of a broader partnership with a magazine like Fantastic Man — that’s worth it. It’s the same concept as wild-posting. You’re spending a fortune to get that Instagram photo, and a print ad serves a similar purpose.

Magazines that get it, like W under Sarah Moonves or Fantastic Man, they know it's about more than just the magazine itself. It’s about throwing great parties, diversifying, creating new verticals, and doing what needs to be done on the agency side. Historically, magazines made ads for brands, so it’s not that different.

For me, Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman are the gold standard. They do a brilliant job of featuring both interesting famous people and niche topics. Their voice is sophisticated yet approachable, and striking that balance is incredibly hard to do.

JW: I used to go to Paris and Milan twice a year specifically for ad meetings. The LVMH and Kering brands are so quick to establish who they think you are — your sensibility, your tone-of-voice, who you’re dressing, who’s on the cover. It’s so competitive, they have to categorise you quickly — are you more like Pop or Love? Or are you closer to Holiday or Luncheon? Standing out and cultivating a distinct identity is difficult.

CB: I think Apartamento and Neptune Papers do it really well. Or Hommégirls, which is underwritten by Chanel. If Hermès or Chanel is supporting you, sponsoring you, it doesn’t matter if it feels a bit more obvious. But I also don’t see that as a problem to begin with. It’s part of the game. It doesn’t affect anything editorial for an advertiser to pay X, Y, and Z — just to dress a celebrity for a cover.

I interviewed this stylist for a Converse project once, and he said, “I like to be put in a box, as long as the box is deep. It gives me guardrails, and I think that’s sometimes what people need.” I don’t think every creative person should be given full license to do whatever they want. Boundaries — or restrictions — can breed greater creativity.

How Long Gone is an hour. We never do more. We never do less. Knowing that, the conversation has to live inside that box. I don’t need to meander for three hours to get something good. Those kinds of constraints can apply to so many different mediums.

In America, people lead with 'this is what I have' rather than 'this is who I am'. Whether it’s their clothes, their cars...guys with three roommates are driving G-Wagons. Our priorities are messed up

JW: That’s interesting. How does fashion consulting fit into your life? What does it look like for a J. Crew, for instance?

CB: It depends, obviously. J.Crew is great because it’s a brand I grew up with. Brendan, the creative director; Spencer, the brand director; and Adam, the art director — they’re all people I get on with really well, and we share a similar way of seeing things.

What I like to do with brands is be available to them as much as they need me. Whether that’s casting, art direction, collaborations, or events—it doesn’t matter. I’m not precious about the role, as long as I’m helping people who are great at what they do to get something over the line, make it more visible, and ultimately drive sales. A lot of creatives tend to have their heads in the clouds — which makes sense, that’s their job. They’re thinking ahead. I see my role as helping ground that vision in reality, without stifling the creativity. Someone — or something — needs to be grounded in reality without stifling creativity.

JW: You’re strategy, as opposed to the creative direction?

CB: I did "creative direct" the last Leon Bridges album. Because I know him and his management, they came to me and asked if I could put something together in a folder. I brought in my talented friends — Jack Bool to shoot, Oliver Shaw for art direction — people I knew could do it best and, honestly, make my job easy. It can be that simple.

Creative direction means so many different things now, depending on who you ask. I don’t have Photoshop. I don’t know how to use Figma. But I know what’s good and what’s bad. And to me, that’s what gets a project to the place where it works.

JW: That’s how we used to present, So It Goes’ agency offering. What are you getting? You’re hopefully getting taste, you’re getting access to a network, you’re getting a point of view. How those things come together — that depends on the project.

CB: Everything means different things to different people, but I’ve established how I operate. Some people love it, and we keep working together.

I also believe that the rolodex — the ability to call or text someone directly — leads to better pricing and faster turnaround, which is incredibly valuable for corporations. If a brand reaches out through a company email, the rate might be five times higher than if I just text that same person. In the long run, it’s a smarter investment to pay me than to do that six times a year and overpay everyone involved.

Rugs at J. Mueser in the West Village

JW: Do you find people understand that instinctively, or you have to explain?

CB: Some people get it. In this space, I’ve never had a traditional job — I’ve always worked for myself. There have been ups-and-downs, times that were leaner than others, but I’ve always figured it out.

There are a lot of people doing what I do, but what sets me apart — aside from age — is that I’m good at navigating the work/social dynamic. I genuinely believe everyone in the room has value. When you come in as an outsider, you have to stay humble and make it clear you’re there to help, not to take over. I’m no more important than anyone else. It’s a collaboration — a level playing field between talented people.

JW: People often feel threatened when an outside consultant or agency is brought in. There’s this sense of, you’re taking my job or you’re doing a version of my job. So part of the challenge has always been finding ways to reassure people—without explicitly saying it — that you’re there to help, not replace.

CB: I’ve had people straight up tell me, “I thought you were going to be an asshole.” And now we’re friends. The nature of this work has changed — it’s much more interpersonal now. It’s about relationships and how you deal with people. My approach brings out the best in others — and that’s what I bring to the table.

JW: The ability to shape a career out of “yes” experiences — and to know your self-worth — feels very specific to the culture in America. Given how much time you spend traveling, do you find that the way you’ve built your career translates to other parts of the world?

CB: London is my favourite place in the world. I’d love to live there — but no one makes money, even the successful ones. There’s this attitude that everyone is creative and somehow owed a job in the industry they desire. But that’s just not true. I don’t need investment bankers trying to write poetry because they read somewhere that they should pursue a creative outlet. I’m not owed this either—I have to make it happen for myself and prove my worth. And if it doesn’t work out, I’ll do something else.

Musicians often complain they can’t make a living touring. Well, maybe your music sucks. Maybe you’re just not popular enough. Not everyone is entitled to a career as a touring artist. So many variables have to align for that to even be possible. This idea that “I can achieve anything” or “I want to earn a lot of money” is uniquely American. In most other places, that ambition is frowned upon.

I go to Stockholm and Copenhagen a lot, and that attitude just doesn’t exist. Everyone dresses the same. No one wants to stand out. And that has its place. But when I travel for work, I respect the culture and customs — I just don’t tone down who I am. I’ve only worked with a few European companies, and I believe it’s because they understood that difference — and liked it. They wanted the American approach, and they knew the only way to get it was to hire me.

There’s this attitude that everyone is creative and somehow owed a job in the industry they desire. But that’s just not true. I don’t need investment bankers trying to write poetry because they read somewhere that they should pursue a creative outlet. I’m not owed this either—I have to make it happen for myself

JW: My friend and co-founder of So It Goes magazine married a Norwegian woman and moved to Oslo. When he initially told her friends what he did for a living, they looked at him like he was insane. What do you mean? No security? No hours? Etc etc. Tall poppy syndrome is very real, country-to-country. But here...you know...the ‘American Dream!’

CB: We joke about it — when you see certain friends you grew up with, or family members, and they call you “Hollywood.” But overall, it’s cool. It’s still cool.

JW: In fashion, there’s this interesting, though pretty cliché, pattern that plays out with young, emerging English designers who show at Fashion Week. For a moment, everyone’s all over them. Then within a year, they go bust because there’s no money behind them.

CB: In Canada, musicians actually have it pretty good because of the grants. All that Broken Social Scene stuff I love — those records were made with Canadian government funding. In Denmark, they practically pay you to have a kid!

JW: Years paid maternity or paternity leave, it’s crazy.

CB: I don’t think either way is right or wrong. There’s just a way that I’m used to.

JW: Would you move to London?

CB: If the situation were right—and I was making American money — I could live in Soho or Mayfair, in a two-bedroom flat, or stay at Dean Street Townhouse right in the centre. I don’t understand why everyone lives an hour outside the city. I just don’t get it. Sure, it’s expensive — but once you’ve lived in New York, nothing feels expensive. Everything else seems cheaper by comparison. I’ve lived in New York for sixteen years, and I don’t even think about it anymore. As soon as I walk out the door, I’m down 100 bucks. Every day in New York is a chance to spend more and more money. But I don’t know where else I’d live. London appeals to me — it’s similar to New York, there’s no language barrier, and it offers everything artistically. But the weather sucks. And then there’s the social nuance, the class system. If you’re not from there, you’ll never really understand how to live there.

JW: Money talks in America.

CB: Money really does talk.

JW: Whereas in the UK, it’s the opposite. Especially for a certain slice of English society!

CB: Yeah, but I hit it off with...those...people immediately. They have great personalities, they’re interesting, and they actually do things. In America, people lead with this is what I have rather than this is who I am. Whether it’s their clothes, their cars… guys with three roommates are driving G-Wagons. Our priorities are messed up. You see the G-Wagon when you go to the grocery store, but you don’t see the fact that they live at home with two other guys.

JW: I wonder if you’re drawn to those people partly because British sarcasm feels familiar to the How Long Gone cadence?

CB: Totally. There’s definitely a mutual fascination with each other’s cultures. You know, former How Long Gone guest Plum Sykes invited us to her country house in the Cotswolds. When I arrived, I was like, yep, this is exactly what I thought it would be. Jason and I got a kick out of it because we’re so American. It’s like there’s nothing more American than a Southerner and someone from California. We’re representing the two classic American archetypes. Hopefully, we’re giving them a good name.

Find out more at howlonggone.com

Chris loves

The Fence Magazine

"This is an independent magazine and newsletter based in London. I don't get all of the references, but I love the writing and the design. It's essential to support independent projects like this, especially when they are of high quality"

Ultra Lights / Ultra Lights EP

"This band is from my hometown of Atlanta, and this excellent EP evokes The Rolling Stones, Wire, and The Modern Lovers"

Durham, North Carolina

"I have visited this charming Southern city a few times to visit my friend Brad Cook, a music producer, and I love it. It's sleepy, warm, easy to navigate, and the food and coffee are better than they should be. It's a short, direct flight from New York City; it's my version of touching grass"

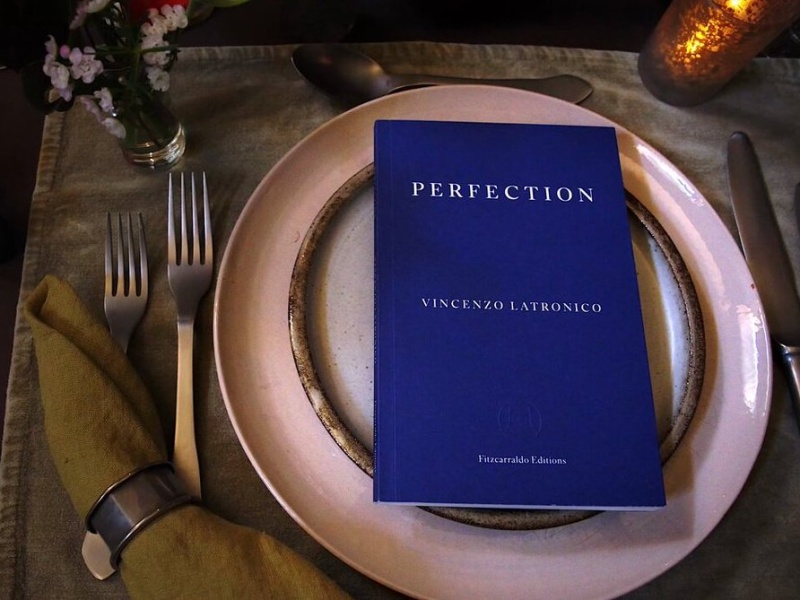

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico

"A quick and easy read that is a clever and scathing skewer of our current moment, delivered with precision and detail"

Click here to check out more features...

Stephen Galloway

Okay Kaya

Jaime Perlman

Jarod Taber

Ottessa Moshfegh

Lorraine Wild

Lorraine Wild

Caroline von Kuhn

Daisy Hoppen

Camille Charrière

Amé Amrit

Indigo Lewin

Steph Wilson

Amanda Charchian

Nick Haramis

Sara Morosi

Stefan Siegel

Kristine McKenna

Johnnie Collins

Lena Felton

Stéphane Sednaoui

Zak Ové

Valentine Avron

Kay Montano

Douglas Dare

Lee Swillingham

Posy Kai Dixon